Poverty

Poverty

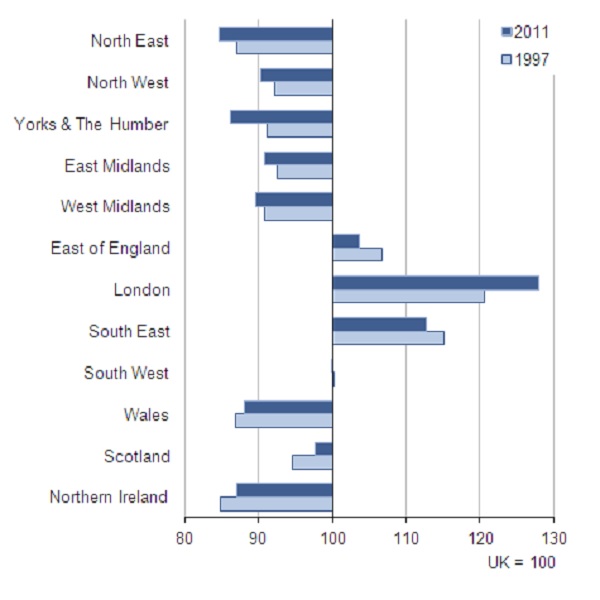

Tucked away in an obscure report on the Office for National Statistics website is a graph that shows, very clearly, how the UK is a divided nation. This graph of Gross Household Disposable Income per head in the UK’s nations and regions, shown below, ought to be a political game changer.

Gross Domestic Household Income by region / nation 1997 and 2011, UK index = 100

The Yawning Chasm

What the graph shows is a gap between the average household income per head in London and the south east of England and almost every other part of the UK. In fact, this is not so much a gap as a yawning chasm – average disposable income per head in London is more than half as great again as in the north east of England, and not far off half as much again as in Wales. In other words, for every £100 enjoyed by someone in London, someone in Wales has just £66.

It’s not just the usual poor relations of Wales, the North East and Northern Ireland that are well behind the UK average. Yorkshire, the North West, the East and West Midlands, even Scotland – all are lagging behind London and the south-east’s run-away wealth. In fact the distribution of income is so polarised that ONLY these two regions plus the East of England have income per head above the UK average. Everywhere north or west of Oxfordshire is below par.

The Widening Chasm

And if all this is not enough, the polarisation between the rich south-east corner of England and the rest is getting bigger. Between 1997 and 2011, a period encompassing boom as well as bust, the gap between London and the south east of England and most of the rest of the UK grew. The north east and north west of England, the midlands and Yorkshire and Humberside all fell even further behind the UK average.

There is one small crumb of comfort here.

In Wales, Gross Disposable Household Income per Head actually grew relative to the UK average over this period. Not by much, admittedly – the gap closed by a mere 1.2 percentage points – but Wales still bucked the trend. Intriguingly, so too did Scotland and Northern Ireland. This raises some questions:

- Might this be the long-lost “devolution dividend”?

- Or perhaps the proof that EU funding made a difference?

It might be nice to think so, although in reality the figures need a lot more analysis before reaching any conclusion.

So What?

This highly unequal pattern matters beyond the pound in your pocket. The vast majority of the UK’s media is produced in London; 12 out of 18 MPs in the Cabinet (excluding the “territorial” Ministers) represent London and South East constituencies; and most UK organisations have their head offices there.

The norms of these key decision-takers and opinion formers are not just those of their social class but also those of place. We see this all too often in media coverage – a flake of snow falling in Kent is headline news while two-foot deep drifts in Gwynedd pass unremarked. But it’s deeper than this. Many policies and priorities are shaped by the skewed circumstances of this prosperous region – think bedroom tax, help to buy housing, and HS2. The assumption is that the rest of the UK is like London and the South East – it isn’t.

Time for regional policy?

From the 1960s to 1990s, massive inequalities between regions were addressed by ‘regional policy’ – a mix of incentives and constraints to shift business activity into various ‘deprived areas’. There was a lively debate then about whether attempting to spread the economic spoils helped the ‘regions’ or hindered UK growth. It seems like the latter view won, as UK regional policy is now so watered down it is virtually negligible. The Industrial Communities Alliance is the sole voice arguing for regional policy these days.

It might be the case that Wales’s economy has benefited from devolution or EU funds, but how much better it would do if it had a helping hand from UK policies that encouraged the spread of economic goodies. In all the talk of ‘re-balancing the economy’ there is no reference to addressing geographical imbalances. Regional policy might not be flavour of the month, but for people in Wales, the north-east of England as well as great swathes of the midlands and north west, it might be a policy whose time has come.

Victoria Winckler is Director of the Bevan Foundation.